Published in Issue 110 of The Leither, my article entitled 'The Legacies of Empire,' about the historic suppression of the indigenous British Isles languages by the English majority.There’s a scene in Monty Python’s Life of Brian where Judean freedom fighters argue the pros and cons of the Roman occupation. Martial law and crucifixions? But there’s sanitation, irrigation, and medicine. Slaves fighting to the death for entertainment? There’s education, public order, roads and wine. Imagine the same scenario during the British Empire. A common language, trade, technological advances, judicial systems? But there’s racism and slave labour. Transport links, hospitals and universities? 26,000 women and children dead in Boer concentration camps; millions starved in famines in Ireland and Bengal. Good or bad, Britain has left an indelible impression on the planet, its Empire the largest history has known. As recently as the 1920s the union flag proudly flew over one-fifth of the world’s countries, with King George V head of state to 460 million subjects. Although the Empire began dissolving after the last world war, British colonialism has left many enduring legacies, foremost of which is the prevalence of the English language. These sentences you are reading are from the third most widely spoken language on earth (outranked only by Mandarin and Spanish.) It has been most successful in America; where, as the speakers of indigenous Native American languages have shrunk from 20 million to 2 million, English speakers have rocketed inversely. The reason that Britain, a country that could fit inside California, came to amass such a vast Empire can be explained easily. Consider the Battle of Omdurman in 1898. The British Army suffered 47 dead. Their Sudanese opponents lost 12,000. The British were armed with rifles, machine guns and artillery. The Sudanese natives waved swords and spears. My culture and my language have the right to exist, and no one has the authority to dismiss that. A fine line can exist between elitism and racism. On matters concerning language and culture, the distance can sometimes cease to exist altogether. The Empire may be long gone but British jingoism remains a potent force; these days the sense of superiority is reinforced verbally rather than with guns. Take Gogglebox, a TV show where you watch viewers watching TV shows. Two participants, Kent hoteliers Dom and Steph Parker, ply themselves with cocktails before opinionating in Daily Mail mode. Watching a political interview on one occasion, Steph claimed foodbanks had nothing to do with Osborne’s paralyzing cuts: there were too many benefit scroungers. The amount English taxpayers forked out to promote the Welsh language once outraged Dom.

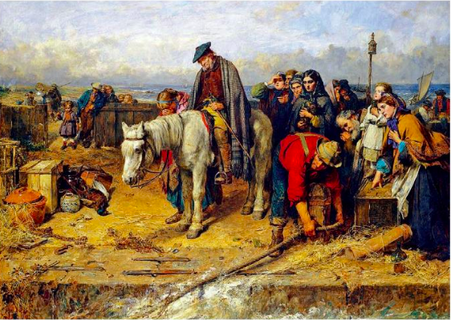

Sneering at those who do not speak received pronunciation (RP) English is another colonial hangover. Since RP is defined as ‘the standard form of British English, based on educated speech in southern England,’ non-RP covers everything from the indigenous British languages (Scots, Gaelic, Welsh, Irish, Cornish and Manx) to regional dialects. Recently Welsh Assembly members raised the issue of their native tongue’s erosion. Many poetic place names have been ousted by dumbed-down Anglicised versions. A 14th century farm, Faerdre, has become Happy Donkey Hill, while a Snowdon mountain, Cwm Cneifion, is now ‘Nameless Cwm’. Apparently English hillwalkers struggled with ‘Cneifion’. I took 10 seconds to check the pronunciation online: “cn-eye-vee-on.” Language lies at the heart of culture, so colonial undermining has often gone much further than accommodating the whims of lazy tourists. The Battle of Culloden in 1746 had a catastrophic impact on Scottish culture. In the aftermath of the Jacobite defeat, the London parliament, bolstering the ruling (German) House of Hanover, introduced legislation aimed at destroying the Highland way of life. Gaelic was banned. A quarter of Scots had been Gaelic speakers, but over the decades this figure plummeted, especially when the Education (Scotland) Act 1872 was passed, which ignored Gaelic completely. Ethnically cleansed from Scotland’s classrooms, Gaelic speakers amounted to less than 3% of the population by the mid 20th century. Fast-forward three hundred years and Scottish languages are still seen as a poor relation. Kevin Williamson, founder of counter-culture magazine Rebel Inc, pointed out that when James Kelman was awarded the 1994 Man Booker Prize for ‘How Late It Was, How Late,’ he was the first Scottish author to have received the accolade since 1969. Even then, The Times described his poignant story of a man blinded by police officers, and written in Glaswegian vernacular, as “literary vandalism”. One Booker judge, Rabbi Julia Neuberger, called the award “a disgrace.” Kelman’s acceptance speech ruffled feathers amongst the dinner-suited RP-speakers at the award ceremony. “My culture and my language have the right to exist, and no one has the authority to dismiss that. A fine line can exist between elitism and racism. On matters concerning language and culture, the distance can sometimes cease to exist altogether.” Irvine Welsh’s monumental debut Trainspotting was withdrawn from the 1993 shortlist because two judges had threatened to resign. It is not inverted snobbery to suggest that, had the story not featured Muirhouse skagboys speaking in Edinburgh dialect, but Oxford undergraduates with substance abuse issues, then (returning to Python) the outcome would have been ‘something completely different.’ |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed