|

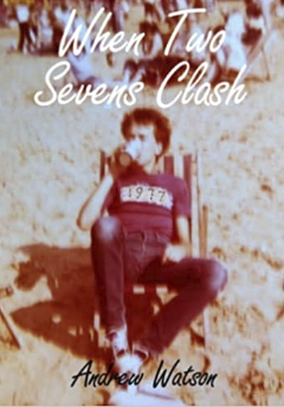

2022. Our oxymoronic ‘United’ Kingdom celebrated Queen Elizabeth’s Platinum Jubilee (the street parties held in many areas conspicuous by their absence in others.) The backdrop to Andrew Watson’s joyride of a novel When Two Sevens Clash, originally published in September 2018, is the Silver Jubilee that similarly polarised the nation in 1977. On the 45th anniversary of the Sex Pistols' inflammatory single, 'God Save the Queen,' let’s turn the clock back. Decades before alleged relationships with trafficked underage girls, Prince Andrew is second-in-line to the throne and supposedly Her Majesty’s favourite. As an institution, the monarchy is embedded in British public life. Against this backdrop of bunting-festooned streets a cultural tsunami has been gathering pace since the tail end of the previous year. In December 1976, Britain’s first ‘punk rock’ records were released. The Damned’s ‘New Rose’ was followed by the more incendiary ‘Anarchy in the UK’ by The Sex Pistols. Although the latter were dropped by their record company, EMI in the wake of a shambolic interview by Bill Grundy on Thames Television, this sealed rather than impeded the Pistols position in the cultural zeitgeist. Proto-punk may have been making waves across the Atlantic for considerable time, courtesy of Iggy Pop and The Stooges, New York Dolls, and The Ramones et al, but now the UK tabloids could delight in sensationalising this teenage craze manifesting in Blighty. While 1977’s punk revolution never threatened to topple the nation’s pop darlings from pole position (Cliff Richard, Boney M, Fleetwood Mac, and Barry Manilow remained the bestselling artists by far), it did herald a significant moment in British pop culture. That new bands are still labelled ‘post punk’ is testament to the enduring influence of that initial detonation. The singer was like one of those blokes ranting at Speaker’s Corner and he sounded like he came from London. And the stuff he was going on about: getting what you want, shopping schemes, council tenancies. It was out of this world but it was very much of this world; it made no sense but it made complete sense; it was wonderful. Many captivating histories, biographies, semi-autobiographies, and novels have described punk’s impact. John Robb’s Punk Rock: An Oral History, Jon Savage’s England’s Dreaming, John Lydon’s Rotten: No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs. Eve Libertine’s Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. John King’s Human Punk. There are many more. When Two Sevens Clash is a worthy addition, a novel based on the first-hand experiences of an impressionable youth ripe for the Damascene moment of being drawn into the nascent punk scene. A 15-year-old from a tower block on an East London housing estate, Billy Monson is poised on the cusp of so many of life’s challenges. He is in his final school year, exams looming that will decide whether he might follow his father into the local biscuit factory or get an office job. (In 1977 only one-in-seven went on to further education, as opposed to today’s one-in-three.) Family life is fractious. After his mother’s death, he doesn’t always get on with his father, especially when a new girlfriend, the Elvis-loving Shirley ‘twinset’ appears on the scene. His wayward sister Deborah’s boyfriend, Mole is also far from trustworthy. Bullies prowl the playground, the estate, and the local football ground, their lumpen violence often an extension of moronic far-right political persuasions. (In the 1977 Greater London Council election, the neofascist National Front were the fourth-largest party, gaining 5.3% of the vote.) Monson seeks solace in reading (George Orwell’s 1984), and listening to his David Bowie LPs. Snapshotting 1977 - Monson’s ‘annus mirabilis/horribilis’ - each chapter is a chronological monthly progression. A cathartic moment occurs in January when best mate Kev plays him a single he’s just bought by The Sex Pistols, “the punk rock group that swore on the local news before Christmas.” This is described thus. “A crash of deafening guitar, a roll of thundering drums and a threatening voice intoning, Right, now! followed by a demonic cackle. The singer started saying he was an anti-Christ and an anarchist and that he wanted to destroy passers-by … and he kept saying he wanted to be anarchy and then he listed things I heard on the news, like MPLA, UDA, IRA, and then he mentioned the NME and then he said he wanted to get pissed and then it all came to a shuddering and chaotic end.” Billy is transfixed. “Excitement. That was the feeling Kev’s record had given me. I had never heard anything like it. It was out of control. The singer was like one of those blokes ranting at Speaker’s Corner and he sounded like he came from London. And the stuff he was going on about: getting what you want, shopping schemes, council tenancies. It was out of this world but it was very much of this world; it made no sense but it made complete sense; it was wonderful.” He watches a TV documentary featuring an interview with The Clash. “The youngest one in the band (Simenon) said the school he went to was no good and the kids learnt nothing … most of his mates were working in factories and he looked angry and sad as he said it. A light had come on in my head; not a light, more an illuminate sign. What the sign said was unclear – the letters were blurred – but it was there and was shining brightly.” Monson succumbs to this light’s allure, getting his hair shorn, ditching ubiquitous flares for straight-legged trousers, customising his shirts with spray-painted and marker pen slogans and band names. In April he travels to a youth club out in the suburbs, in Bromley in Essex. “I knew two good things about Bromley. It was where David Bowie grew up. Secondly, I had read in Sounds about a goup of people called the Bromley Contingent who were the first fans of the Sex Pistols.” In between ‘Play That Funky Music’ and Rose Royce, he pogos to the Pistols with mates Kev and Lorraine, only to be forced to leg it from punk bashers. On the last day of the Easter Holidays before going back to school he sneaks out to a punk club where X-Ray Spex are headlining. “The guitars were fast and loud and the saxophone wailed at the same speed. I was used to hearing saxophones on Bowie’s records but they never sounded like this. It was wonderful.” Punk has so often been described through the prism of England’s art scene of the mid-to-late 1970s, with Vivienne Westwood waxing lyrical about outlandish fashion trends for aspirational outsiders. Watson’s semi-autobiographical approach tells of a demographic far more ripe for its DIY ethos of customising clothes, learning three chords/starting a band, opposing racism and sexism: disaffected kids from inner city housing estates. There is the thrilling backdrop of collecting inspirational new singles. “I had bought the Sex Pistols’ ‘Pretty Vacant’ and ‘Sheena is a Punk Rocker’ by The Ramones, but it was the singles I had by small groups like The Users, The Cortinas and The Adverts that really excited me.” He is also galvanised by literature giving ‘angry young men’ from working class England a voice, like Allan Sillitoe’s The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner and Saturday Night and Sunday Morning.

Later that summer he finds himself swept up in the crowds opposing a National Front march. By September he is going down the well-travelled path of forming his own band, shortlisting names: The Mysterons, The Bored, Rebel Rebel, Daktari, The Useless. The following month, The Sex Pistols (now signed to Virgin) release their long-anticipated debut album Never Mind The Bollocks. The snotty outsiders are now being lauded as one of the biggest bands in rock ‘n’ roll, although their decision to sack songwriting bassist Glen Matlock for Johnny Rotten’s iconic but hopeless mate Sid Vicious has already sealed their fate. He heads to Croydon to watch Siouxsie and the Banshees supported by The Slits. “Mags had mentioned they had done a session on John Peel. They had sounded frantic and sang about stealing from shops and obsessive boyfriends. The Slits were fantastic, chaotic and energetic.” In November, settling for Mormon in Chains, covering The Ramones and penning their own ditties, Billy’s band gig but an issue with borrowed gear has far-reaching consequences. When Two Sevens Clash paints a vivid picture that will resonate with those of us, well into middle-age, who can empathise with Billy’s lightning rod moment of hearing The Sex Pistols for the first time. Punk has so often been described through the prism of England’s contemporary art scene of the mid-to-late 1970s, with Vivienne Westwood waxing lyrical about outlandish fashion trends for aspirational outsiders. Watson’s semi-autobiographical approach tells of a demographic far more ripe for its DIY ethos of customising clothes, learning three chords/starting a band, opposing racism and sexism: disaffected kids from inner city housing estates. This wonderful semi-autobiographical novel give us the point-of-view from the small knot of fans who fell in love with the original punk wave, pioneers drawn into the vortex of a scary but inspirational storm, witnessing early gigs by The Clash, X-Ray Spex, Siouxsie and the Banshees, and many others; musicians (often only just) and artists driven by a fierce urge to express themselves and rise above the grey banality of 1970s Britain. As the Silver Jubilee becomes Platinum, perhaps a key point is the extent to which little has really changed. For all the indie hopefuls who sprung up as punk’s quickly extinguished firework display evolved into infinitely more ambitious and exploratory post-punk, the charts are still dominated by mainstream musical tastes. The UK establishment remains as indomitable as ever, with devious Princes quietly shifted into the background with hush money. Nevertheless, When Two Sevens Clash seizes a golden year and, without a shred of sentimentality, provides a fabulous snapshot, preserving this moment for posterity. Dripping with authenticity, anger, naivety, hope, pathos, disillusionment, but driven by optimism, it shows how cathartic moments can shape young lives. When Two Sevens Clash is available as a paperback as well as a Kindle. #punk #Bowie #TheClash #London #newfiction #comingofage #70s #seventies |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed