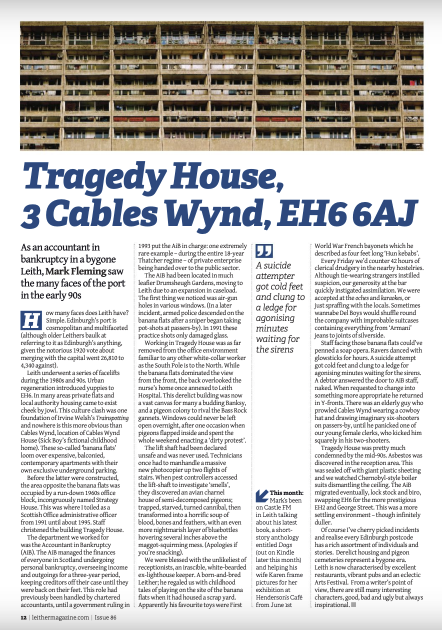

Published in Issue 86 of The Leither, my article about how working as a Leith-based civil servant took me into early-90s Trainspotting territoryHow many faces does Leith have? Simple. Edinburgh’s port is cosmopolitan and multifaceted, although older Leithers baulk at referring to it as Edinburgh’s anything, given the notorious 1920 vote about merging with the capital went 26,810 to 4,340 against. Leith underwent a series of the facelifts during the 1980s and 90s. Urban regeneration introduced yuppies to EH6. In many areas private flats and local authority housing came to exist cheek by jowl. This culture clash was one foundation of Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting and nowhere is this more obvious than Cables Wynd, location of Cables Wynd House (Sick Boy’s fictional childhood home). These so-called ‘banana flats’ boom over expensive, balconied contemporary apartments with exclusive underground parking. Before the latter were constructed, the area opposite the banana flats was occupied by a run-down 1960s office block, incongruously named Strategy House. This was where I toiled as a Scottish Office administrative officer from 1991 until about 1995. Staff christened the building Tragedy House. The department we worked for was the Accountant in Bankruptcy (AiB). The AiB managed the finances of everyone in Scotland undergoing personal bankruptcy, overseeing income and outgoings for a three-year period, keeping creditors off their case until they were back on their feet. This role had previously been handled by chartered accountants, until a government ruling in 1993 put the AiB in charge: one extremely rare example, during the entire Thatcher regime, of private enterprise been handed over to the public sector. The AiIB had been located in much leafier Drumsheugh Gardens, moving to Leith due to an expansion in caseload. The first thing we noticed was airgun holes in various windows. (In a later incident, armed police descended on the banana flats after a sniper began taking pot-shots at passers-by). In 1991 these practice shots only damaged glass. Working in Tragedy House was as far removed from the office environment familiar to any other white-collar worker as the South Pole is to the North. While the banana flats dominated the view from the front, the back overlooked the nurse’s home once annexed to Leith Hospital. The derelict building was now a vast canvas for many a budding Banksy, and a pigeon colony to rival the Bass Rock gannets. Windows could never be left up overnight, after one occasion when pigeons flapped inside and spent the weekend enacting a dirty protest. The lift shaft had been declared unsafe and was never used. Technicians once had to manhandle a massive new photocopier up two flights of stairs. When pest controllers accessed the shaft to investigate smells, they discovered an avian charnel house of semi-decomposed pigeons; trapped, starved, turned cannibal, then transformed into a soup of blood, bones and feathers, with an even more nightmarish layer of bluebottles hovering several inches above the maggot-squirming mess. (Apologies if you’re smacking.) A extremely rare example, during the entire Thatcher regime, of private enterprise been handed over to the public sector. We were blessed with the unlikeliest of receptionists, an irascible, white bearded ex-lighthouse keeper. A born-and-bred Leither, he regaled us with childhood tales of playing on the site of the banana flats when it had housed a scrapyard. Apparently, his favourite toys were First World War French bayonets, which he described as four feet long ‘Hun kebabs.’

Every Friday we’d counter 42 hours of clinical drudgery in the nearby hostelries. Although tie-wearing strangers instilled suspicion, or generosity at the bar quickly instigated assimilation. We were accepted at the oches and karaokes, or just spraffing with the locals. Sometimes wannabe Del Boys would shuffle around with improbable suitcases containing everything from ‘Armani’ jeans to joints of silverside. Staff facing those banana flats could’ve penned a soap opera. Ravers danced with glowsticks for hours. A potential suicide got cold feet and clung to a ledge for agonising minutes waiting for the sirens. A debtor answered the AiB staff, naked. When requested to change into something more appropriate, he returned in Y-fronts. There was an elderly guy who prowled Cables Wynd wearing a cowboy hat and drawing toy six shooters on passers-by, until he panicked one of our young female clerks, who kicked him squarely in his two-shooters. Tragedy House was pretty much condemned by the mid-90s. Asbestos was discovered in the reception area. This was sealed off with giant plastic sheeting and we watched as workers in Chernobyl-style boiler suits dismantling the ceiling. The AiB migrated eventually, lock stock and biro, swapping EH6 for the more prestigious EH2 and George Street. This was a more settling environment – though infinitely duller. Of course, I have cherry picked incidents and realise every Edinburgh postcode has a rich assortment of individuals and stories. Derelict housing and pigeon cemeteries represent a bygone era. Leith is now characterised by excellent restaurants, vibrant pubs and an eclectic Arts Festival. From a writer’s point of view, there are still many interesting characters, good, bad and ugly but always inspirational. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed