|

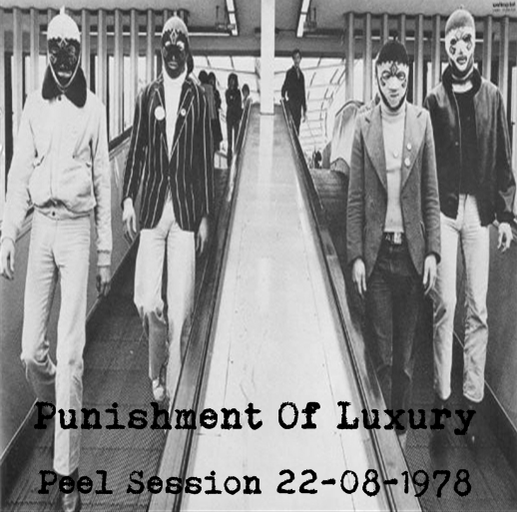

August 30th is the birthday of legendary DJ John Peel who passed in 2004, aged 65, and would've been 81 today. I got the title for my biography, BrainBomb, from a song by Punishment of Luxury, one of the countless lesser-known bands he championed on his long-running BBC Radio 1 show. One of the chapters in BrainBomb is entitled 'John Peel,' and deals with the way rediscovering my love of music, in particular post-punk, was so integral to my recovery after a spell of severe depression had led to me being sectioned. The dorm light is extinguished, leaving only the orange aura highlighting the fire exit. Andy is already heavy breathing, his manic routine of pacing the ward succumbing to fatigue. I fumble for the Walkman, slotting the headphones in. I then grasp one of the cassettes Anne handed over during the evening’s visit. There are a dozen or so in a John Menzies carrier bag. As well as compiling a couple of mix tapes, she dug out some of my John Peel recordings. As I poke the cassette into place, my mind drifts to a book about Dachau concentration camp I once browsed through in the Napier College library – a slim but powerful volume any Holocaust denier should’ve been forced to read with their eyes prised open, Clockwork Orange-style. The book covered the rise of Hitler’s cult, from Brownshirts, book pyres and ‘Kristallnacht,’ through to obscene images of children being led away to ‘showers,’ mounds of emaciated corpses and the aftermath of human guinea pigs being used in failed medical experiments. But one photograph that blew my mind depicted prisoners in their striped overalls escorting one of their own to the gallows. They were all playing instruments; some had violins, others accordions. The appalling irony. The only time the inmates would’ve heard music drifting over the horrific camp was when someone was being led to their death. Other than that brief outburst of melody, the wretched existence of the Third Reich’s brutalised prisoners would’ve been characterised by crushing silence, broken only by orders barked in an unfamiliar language, guard dogs snarling, jackboots pounding, frequent rifle cracks, a rope jerking. Music and silence. Life and death. Around the same time I wrote a philosophy essay about music. I still recall some of the quotes I used. Leo Tolstoy: “Music is the shorthand of emotion.” Jane Austen: “Without music, life would be a blank to me.” Jack Kerouac: “The only truth is music.” My finger jabbing ‘play’ brings me back, ready to quash the silence. After so long in a self-enforced, noiseless bubble of apathy, into the universe of possibilities, aural sensations. Sensual overload. The hiss of the blank tape, John Peel’s voice, muffled, indistinct, but era-defining. As intrinsic a part of my formative teenage musical tastes as the music itself. I was fortunate to meet him last year and still beam thinking about the moment our paths crossed. I was making my way to a bus stop in Princes Street when I spotted him, just ahead. Catching up, I called out, "John Peel?" About turning, he nodded. We shook hands. There, in Edinburgh city centre, John Peel and I chatted for five minutes. He was on his way to Waverley Station after watching New Order at the Playhouse. I gushed about how much I loved his radio show. This would be a spiel he must’ve heard a thousand times, but he was so self-effacing and unpretentious he just smiled modestly, engaging with me as if I was an old friend. After we parted I realised I’d forgotten to mention Little Big Dig. If I’d had a demo on me, I know he would’ve gladly accepted it, probably giving it a listen during his journey. Championing new music is in his DNA. If the dark, the yin, is represented by Stiff Little Fingers’ songs of barbed wire and Armalite rifles, The Undertones are the yang, the light, enthusing about excitement and first crushes. Teenage Kicks. Fittingly, the compilation commences with his avuncular tones introducing The Undertones, then the strident introductory riff to ‘Listening In,’ from a Peel session I recorded in January 1979, when listening into his show was a distraction from school in the morning. The euphoric fusion of power chords and melody, underpinned by Feargal Sharkey’s falsetto voice, the sound Peel adores and insists he wants played at his funeral. Set against the insane backdrop of ‘the Troubles,’ the Derry band provide a snapshot of joy. If the dark, the yin, is represented by Stiff Little Fingers’ songs of barbed wire and Armalite rifles, The Undertones are the yang, the light, enthusing about excitement and first crushes. Teenage Kicks. Immediately I’m transported to my bedroom, hooked on these sounds as they are being beamed live, my homework abandoned. I harness the memory. As I bask in the beautiful punk-pop, I can see the pencil marks by the door which gauged childhood bursts in height. Amongst the posters and ticket stubs, traces of blu-tack are also visible in the white woodchip wallpaper, a ghostly constellation indicating where older posters hung. In my mind I pin these up again: Black Sabbath’s ‘Technical Ecstasy’; Gene Simmons of Kiss, stage blood drooling from his tongue; then, my teenage musical tastes having undergone this seachange, clippings of every band from Alternative TV to Zounds, scissored from Sounds and NME. I think about the countless hours I escaped by listening to John Peel, how the tastes of a 48-year-old Merseysider were so influential on a Scottish lad a couple of decades younger. I would wait in anticipation, fingers poised on the play/record buttons of my HiFi, safe in the knowledge he never spoke over the intro or outro of any songs, allowing perfect compilation cassettes. I’ve dozens of tapes at home, reflecting the man’s gloriously eclectic tastes: punk, post-punk, reggae, metal, industrial, dance, electronica, soul, hip-hop, indie… every type of pop music from dream pop, psychedelic pop, and African pop to Iggy Pop. Next, from a session recorded in November 1978, just over nine years ago but still sounding fresh, Crisis. ‘White Youth.’ The title sounds like they could be some hideous far-right band, barking Aryan supremacist gibberish. But the sentiment is the polar opposite. Barely punk at all in its delivery, it’s subtle, dynamic, employing single notes and harmonics, not bar chords. The emphatic chorus says it all: “We are black, we are white, together we are dynamite.” Peel’s voiceover states: “Well, I must say that of all the contemporary varieties of rock music, it’s this basic and direct variety that I like the best myself.” |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed