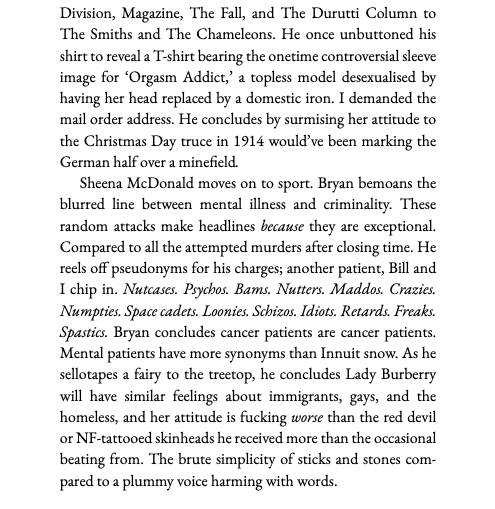

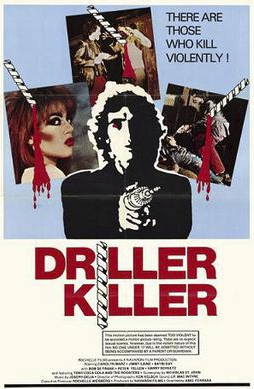

Like the blood red legend imprinted throughout a stick of rock, mental instability runs through so many horror storylinesA psychological drama rather than horror, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest had horrific moments. But horror films set inside mental hospitals are an entire sub-category of the genre. For horror screenwriters, mental illness equates to danger. Movies and Netflix series are infested with unhinged characters. Mad scientists. Mentally damaged Appalachian hillbillies. Psychiatric institution escapees in William Shatner masks. In Milos Forman's One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975), a convict, Randall McMurphy (Jack Nicholson) is placed in a mental facility to determine if he is suffering from a genuine psychotic condition or feigning this to avoid prison labour. After rebelling against the head nurse's stern regime, he ends up, literally, losing his mind through medical procedures. A psychological drama rather than a horror movie, McMurphy's demise was nevertheless horrific. In another outing, The Shining (1980), adapted from bestselling author Stephen King's third novel, Nicholson plays a hotel caretaker who suffers a mental breakdown inspired by supernatural forces, eventually 'going mad' and becoming intent on butchering his family. Horror films set inside mental hospitals are an entire sub-category of the genre. Shock Corridor (1963). The Ward (2010). A Cure for Wellness (2016). Asylum (1972), sharing its title with the 2nd series of the American Horror Story anthology. Stonehearst Asylum (2014). Session 9 (2009). Unsane (2018). Gonjiam: Haunted Asylum (2018). The Ninth Configuration (1980), written by William Peter Blatty, who also penned The Exorcist, an inspiration for Martin Scorsese's Shutter Island (2010). Just as McMurphy's condition initially seems ambiguous, in the real world, not everyone claiming to be mental is actually mental. The emotive word can simply be a euphemism for recklessness rather than behaviour warranting psychiatric intervention. Scottish teenagers have long added 'mental' to gang names as shorthand for warning rivals of their propensity for violence: Young Mental [scheme name.] (Here, it's important to point out the correlation between gang membership and actual mental health issues is an entirely different subject, and a central theme of Airdrie writer, Graeme Armstrong's outstanding debut novel, The Young Team.) Undefinable madness The most captivating stories rarely concern people coasting through untroubled lives. Central characters are more likely to be on the edge, taking out their seething inner turmoil on others, verbally or physically. But in any context, what constitutes mental instability is a perplexing, age-old question. Serial killers, considered madmen by the majority of society's sane individuals, sometimes blame phantom voices for their horrific actions. In 1970s New York, David ‘Son of Sam’ Berkowitz, heard demons. In 1980s Yorkshire, Peter Sutcliffe heard God. Was Colonel Paul Tibbets a madman for piloting the B-29 named after his mum, Enola Gay, over Hiroshima, a Japanese city populated by civilians, 20,000 Korean slaves and US POWs, then dropping the hilariously ironic 'Little Boy' atomic bomb to incinerate them all? Writers have often addressed the correlation between madness and warfare. Kurt Vonnegut used his sixth novel, Slaughterhouse-Five, to describe his experiences of being a US POW in WW2, where he witnessed both the firebombing of Dresden, resulting in the deaths of 25,000 of its citizens, and the execution of an American soldier for looting a teapot from the charred rubble. In Joseph Heller's Catch-22, the central protagonist, Yossarian, forced by his recklessly social climbing superior to fly excessive combat missions, wrestles with a dilemma. “If one is crazy, one does not have to fly missions; and one must be crazy to fly. But one has to apply to be excused, and applying demonstrates that one is not crazy. As a result, one must continue flying, either not applying to be excused, or applying and being refused.” For horror screenwriters, tapping into unbalanced minds is a 'go to' plot device. But as Barry Katz, PhD, a forensic and clinical psychologist with the West Essex Psychology Center, New Jersey, has stated. "In the movies, people with mental illness are literally seen as monsters and dehumanized. This takes fears and lack of understanding people already have and exploits them by presenting a narrative in which the individual is threatening or scary." In my memoir, 1976-Growing Up Bipolar, I address society's stigmatised attitude to mental health issues in a chapter entitled Psychos. Writers of horror can mine the human mind on a more visceral level, poking at our deepest fears of danger. Of what lurks in the dark. This is why, on a purely entertainment level, I love watching horror films. As teenagers, whenever anyone had a free house (an empty), word would spread like wildfire. Carryouts were purchased. 18-certificate videos were rented from Blockbuster. You always had one mate who could get his hands on grainy Nth generation copies of titles from the wave of so-called ‘video nasties’ banned in the 1980s. Driller Killer. Cannibal Apocalypse. I Spit on Your Grave. SS Experiment Camp. That latter title is a reminder that few stories conjured by a fantastical writer's vivid imagination come close to matching the horrors clinically sane humans are capable of inflicting on each other. But we’re approaching Halloween and the shops are rammed with the trappings to festoon kids’ fancy dress parties. In the run up to October 31st, my daughter suggested popping names of horror films into a hat (a plastic pumpkin hat!) We draw a film at random, then find it on a streaming service, satiating ourselves with films of every sub-genre of horror every other night. So far we’ve been alternately scared witless and enjoyed a gory potpourri including Alien, Monster House, Carrie (the 1976 original), The Amityville Horror (the 2005 remake), Friday 13th (the 1980 original), and The Corpse Bride. With Halloween refreshments.

Horror can be fun! |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed