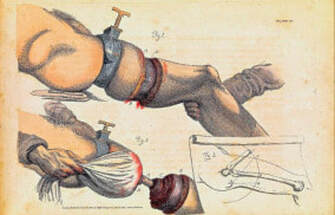

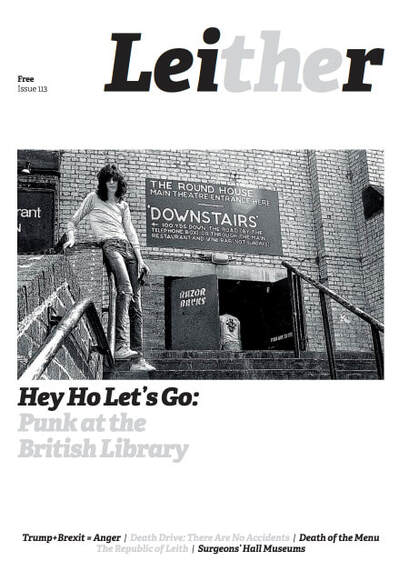

Published in Issue 113 of The Leither, my article about Surgeon's Hall Museum, and women's fight to enter the medical profession in Victorian timesThose of a certain vintage will recall Blake's Seven, the cult 70s TV show about intergalatic freedom fighters. A less well-known but far more revolutionary group existed in reality: Sophia Jex-Blake's Edinburgh Seven. In 1869 Sophia and her six compatriots were studying medicine at Edinburgh University at a time when most of the establishment considered the idea of women undergraduates, let along doctors, preposterous. One Friday the women were due to sit an anatomy exam at Surgeon's Hall when they were confronted by a mob who pelted them with debris. But such was the public disgust at what became known as the 'Surgeon's Hall Riot' that the Edinburgh Seven gained nationwide sympathy, including the support of one Charles Darwin. By 1892, Edinburgh and other universities began accepting female students. Now a museum, Surgeon's Hall opened to the public after extensive renovations last autumn, and the Edinburgh Seven were the subject of a celebratory musical marking the occasion. The architect William Playfair designed the building in 1832 to accommodate two huge collections of specimens donated by anatomy demonstrator John Barclay and professor of surgery Charles Bell, as well as all the latest scientific instruments, anaesthetic equipment, photographs, laboratory slides and X-Rays. A museum devoted to surgery, pathology and anatomy often requires a strong stomach – under 16s must have adult accompaniment. To the layperson, many of the exhibits do resemble something from science fiction. Random pieces of diseased tissue suspended in preservative can have an otherworldliness: you approach a few of the jars with trepidation, gazing in awe at alien-looking body parts distorted even further by cancerous growths. But you are more likely to be struck by the uncanny beauty of the displays. After all, most of what you are seeing is what lies beneath all of our skins. Such was the public disgust at the Surgeon's Hall riot, the Edinburgh Seven gained nationwide sympathy, including the support of Charles Darwin In the 19th century, understanding human biology required the inner workings of bones, muscles and organs to be captured in detailed sketches and paintings, stunning examples of which are posted throughout. John Struthers, President of the Royal College of Surgeons from 1895-97, injected coloured wax into blood vessels, revealing networks of veins and capillaries in breathtaking intricacy. Paintings by Charles Bell depict wounds sustained by redcoats at the Battle of Corunna during the Peninsular War (1809). Decades before the invention of anaesthetic, the only way to avoid infection was for wounded soldiers to take a shot of brandy before surgeons hacked off limbs with a saw. One in three survived.

At a time when warfare was traditionally reflected in art in all its pomp and circumstance – bright uniforms, heroic sacrifice, colourful flags of Empire – these canvasses reveal the truth: the sheer carnage lumps of metal travelling at high velocity inflicted on skin and bone. Other paintings unflinchingly expose general medical afflictions: one man copes with a tumour half the size of his head. Were he alive today Channel 4 would be offering him a starring role in The Undateables. The History of Surgery Museum offers an insight into Edinburgh's unique contribution to surgery. Each stage of the development of the science is highlighted, especially the cornerstone work of Joseph Lister, pioneer of antiseptics (his peers scorned his theories, demanding to know why they couldn't see these microbes he was fighting) and James Young Simpson, the Bathgate-born obstetrician who investigated the anaesthetic properties of chloroform (courageously using himself as the first-ever guinea pig to test the potentially dangerous chemical.) There is also an interactive dissection table, and an ongoing programme of lectures and temporary exhibitions. The autumn schedule includes seminars celebrating the 20th anniversary of the cloning of Dolly the Sheep, while a current exhibition focuses on the search for cancer cures across the globe, from the Arctic to the Amazon. The museum also dwells on darker history, such as Edinburgh's 'body snatching' scandal, when the notorious Burke and Hare sold 16 victims of a serial killing spree to anatomy lecturer Dr Robert Knox, charging £10 per cadaver. A glass case displays a notebook made from Burke's skin after he had been hanged then dissected. (Hare turned 'King's Evidence', gaining immunity from prosecution by squealing like a canary.) There is also a newspaper report of Burke' public hanging: every time his dying body jerked on the rope, the 20,000 crowd roared triumphantly. The upper floor houses the Wohl Pathology Museum. Every item on display, whether that is a minor's skeleton cruelly deformed by scoliosis, a miner's lungs blackened by coal dust, or a heart with a livid knife puncture, represents a real person with a poignant back-story. But there is a hugely important bigger picture. This display of human remains is not like some Victorian sideshow. It is a celebration of the centuries of pioneering research and scientific innovation that lie at the heart of medicine as it is continually being honed in hospitals around the world today. By medical professionals of all genders. Comments are closed.

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed